“ReTown is a community-centric concept,” explains ReTown President & Managing Director Jim Louthen. “We truly believe that when we look at the greater good for all of the people involved in both the private and public sectors, the decisions about what to build and where and why become easier.”

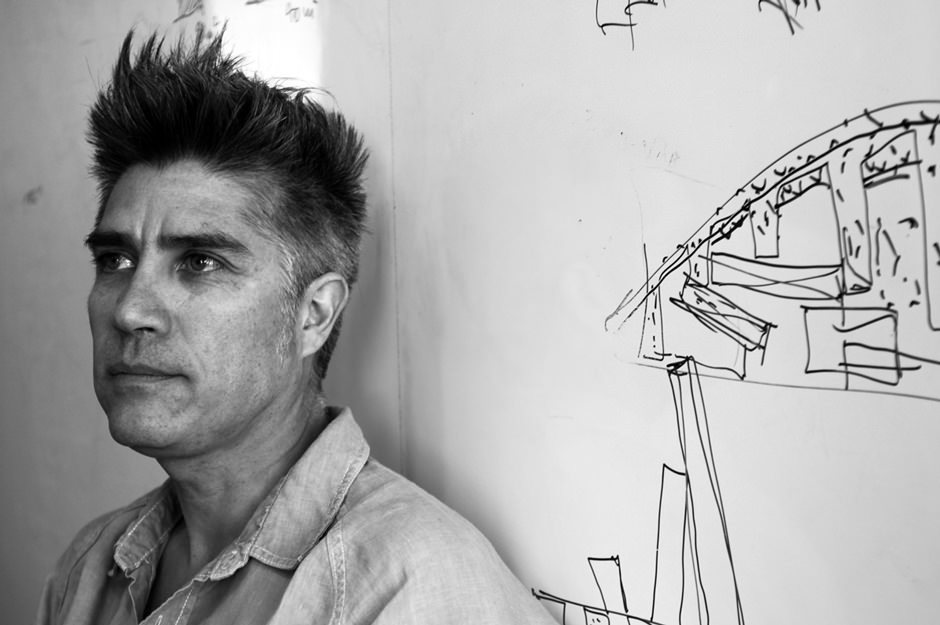

Alejandro Aravena is Executive Director of Elemental, a socially-motivated architectural practice based in Santiago, Chile.

One of the popular figures in architecture today, largely because of his populist and pragmatic views, is Alejandro Aravena of the Chilean firm, Elemental. Alejandro has been involved with numerous notable projects in his own country and around the world, including Elemental’s redevelopment of the city of Constitución, Chile, following a massive earthquake there in 2010. The redevelopment features Elemental’s now renowned “half-houses,” built with sound economics and sustainability in mind.

An Elemental philosophy: Rather than build a bad house, build half of a good house.

Following are a re-post of a story about Alejandro and Elemental from The Guardian, and a re-post of a story from Arch Daily about Alejandro’s talk at the prestigious TED conference, representing thought leaders in technology, design, education, and design.

Like everyone in Constitución, Alejandro Hormazabal remembers exactly where he was in the early hours of 27 February 2010. “I was at home with friends, having a little party. We were on our fifth glass of rum of the night,” he recalls with a smile. “Suddenly, the walls started to sway, and it was nothing to do with the alcohol. The whole house was moving back and forth. And it was moving in circles too, like it was being pulled by a centrifugal force. It was impossible to stay on your feet.”

For around three minutes, Hormazabal and his friends were in thrall to one of the biggest earthquakes ever recorded. With a magnitude of 8.8, it was 500 times more powerful than the one that devastated Haiti weeks earlier; its force was felt across a huge swathe of southern and central Chile,wrecking houses, bridges, railways, roads – and lives.

When the shaking finally stopped, Hormazabal ran across the road to his parents’ house. They were shaken and scared, but alive. Wary of the threat of a tsunami, they all headed for higher ground through the city’s darkened streets.

Eighteen minutes later, the tsunami struck. Six-metre-high waves swept in from the Pacific, up the estuary of the River Maule, and smashed into La Poza, the riverfront district of Constitución. “It sounded like a train coming. Boom! Boom! You could hear each wave as it hit,” Hormazabal recalls.

A rescue worker searches for survivors in Constitución. Photograph: Ivan Alvarado/Reuters

As dawn broke, he headed back to his house. “There were just six floor tiles stuck to the concrete floor, and that was it. Everything else had gone. I cried, I felt impotent. I remember I smoked three cigarettes one after the other. I wandered the streets and found my neighbours, who’d also lost their houses. We went to the boat house, one of the few buildings still standing in La Poza. And we got straight to work that morning.”

For three months, Hormazabal lived in the boat house. He slept on a mattress on the floor and helped distribute food, water, clothes and emergency shelters to his fellow homeless. Between them, the quake and tsunami killed more than 500 people in Chile – around a quarter of them in Constitución. With no electricity or clean water, first-aid facilities in the city were rudimentary. The injured had to be taken to Talca, the regional capital, or to the national capital Santiago, nearly 200 miles away. Both cities were themselves reeling from the impact of the quake.

As the days passed, Hormazabal pondered the future of his home city. How would Constitución recover, and how should it be rebuilt?

In Santiago, Andrés Iacobelli was asking himself the same questions. Days before the quake, Iacobelli had been named Chile’s undersecretary of housing. Now, before he’d even got his feet under the desk, the country faced a monumental rebuilding task.

Iacobelli realised the state couldn’t do it alone and needed help from the private sector. So he spoke to Arauco, a major forestry firm that employs thousands of workers in Constitución, and to his friend and former colleague Alejandro Aravena, an architect atElemental, which specialises in social housing projects. Within days, a plan for Constitución started to emerge.

In early March, Aravena flew to the city by helicopter, surveying the devastated coastline for himself. He arrived to find a city on its knees: “It was shocking. The destruction was on a continental scale.”

“Constitución was without electricity for five days and without running water for 20 days,” explains Fabián Pérez, who was working for the town council at the time. “There were five banks in town and for a month, all of them were closed. There was no supermarket, no business. The city was dead.”

Arauco agreed to finance a “sustainable reconstruction plan”, known by its Spanish acronym PRES. Elemental would oversee the plan’s implementation – but they would do so by consulting local people, as citizen participation was to be paramount. Elemental brought in a consulting firm, Tironi Associates, to advise on this participatory approach, and Arup, a London-based engineering and design multinational. State input came from both the local and regional governments, plus the housing ministry in Santiago.

The team set themselves a target: 100 days to draw up the PRES. “That’s an eternity if you’re living in a place that’s been devastated, but it’s very little time to redesign an entire city,” Aravena says. In total, the PRES projects were budgeted at $150m, 70% of which would come from the state.

Early in the process, Elemental built an “open house” in the city’s main square and made sure their ever-evolving plans were on display there. Anyone could drop in, take a look and make suggestions. There were regular meetings to which the people of Constitución were invited. “I went to every one,” says Dolores Chamorro, a 78-year-old who has lived through her fair share of Chilean earth tremors. “It was fantastic, having these young architects come in to really make us think about the kind of city we wanted.”

One of the most pressing and delicate problems was what to do about La Poza, which had borne the brunt of the tsunami. More than 100 families had lived there, and most had lost their houses. Some wanted to rebuild in the same place. Others wanted to move, but only if they could sell their plots of land. Still others had been living in the area informally and had no plots to sell. It was a complex situation, and Juan Ignacio Cerda from Elemental says many of the public meetings were charged with anger, mistrust and accusations.

“Many of the fishermen were reluctant to give up their plots of land because they wanted to stay by the river, where they worked and where their families had lived for generations,” Cerda says. “There were also a few richer families who had prime real estate on the river front; they too were reluctant to move.”

Elemental came up with three options. Firstly, the destroyed land could be left fallow – the easiest, quickest and cheapest solution. Secondly, a protective wall could be built between the estuary and the city. La Poza could then be re-inhabited, with houses built behind the wall. Thirdly, La Poza could be expropriated and turned into a forest, with the trees acting as a buffer against future tsunamis.

Constitución’s citizens were invited to vote on these options. They chose the forest which, according to Aravena, was wise. “If we had just left the land fallow and banned all future building, people would have inhabited it anyway – illegally and without controls. They would have been very vulnerable to tsunamis,” he says. “The protective wall was the choice favoured by the big construction firms for obvious reasons – they would have got to build it, and also the houses behind. But the experience of the Japanese tsunami of 2011 showed us that protective walls don’t always work. They can’t withstand the force of nature. A forest, on the other hand, doesn’t try to resist the power of a tsunami. It dissipates the impact instead. In the face of geographical threats, you have to find geographical solutions.”

And so La Poza, along with Orrego Island – a sliver of land in the estuary directly opposite – was expropriated by the state at a cost of $20m. Work has now begun on sculpting an undulating forest floor to be planted with pine and eucalyptus trees; Cerda estimates these trees and hillocks will dissipate between 40% and 70% of the power of any future tsunami. Escape routes, lit by photo-voltaic lighting, will be built through the forest so people can get out quickly if disaster strikes again.

The forest will also serve another purpose – increasing public space in an otherwise cramped city. Aravena says that before the earthquake, there were 2.2m2 of public space for each of Constitución’s 50,000 inhabitants. Once the plan is fully implemented, there will be 6.6m2.

The forest will also serve another purpose – increasing public space in an otherwise cramped city. Aravena says that before the earthquake, there were 2.2m2 of public space for each of Constitución’s 50,000 inhabitants. Once the plan is fully implemented, there will be 6.6m2.

Another sensitive issue was what to do about Constitución’s wood pulp mill. The city sits on the edge of Chile’s vast forestry plantations, with much of the area carpeted by pine and eucalyptus. In the city, Arauco owns a mill that manufactures pulp for the packaging industry. It’s an eyesore, built in the 1970s very close to the city centre, which belches out steam and noxious odours.

But the plant and Arauco’s nearby sawmills are also the lifeblood of Constitución, employing 3,000 people directly and 10,000 indirectly. A quarter of the city’s inhabitants rely on Arauco for their livelihoods.

The company was badly hit by the tsunami, too. One of its sawmills was flattened. Workers on the night shift managed to escape by scrambling up a steep hill to safety. The pulp mill was also badly damaged: drenched in seawater, it had to be completely rewired and was out of action for three months.

In the weeks after the tsunami, some residents argued this was the perfect opportunity to move the mill out of Constitución. Aravena describes the issue as “the elephant in the room”; the company was reluctant to consider it, but eventually agreed it should be discussed. “We explained that if we moved the mill, we wouldn’t just move it a couple of miles,” says Charles Kimber, Arauco’s director of corporate affairs. “We would move it a long way south, and Constitución would lose jobs. That effectively ended the conversation.”

Still, Aravena insists, it was important to have demonstrated that the company was willing to listen to the local community – essential for building trust.

Once that hurdle had been overcome, Arauco made important concessions, including spending $10m to reduce odours from the plant. These days, even the most sceptical residents admit the wood pulp smells (which resemble rotting cabbage) are not as bad as they were. Arauco also resolved to tackle the problem of transport noise, and to use excess steam from the plant to heat a series of open-air swimming pools that are due to be built on the seafront. Currently the steam is wasted, simply pumped out into the air over the city.

“Our community relations have improved since the earthquake,” Kimber says. “We realised we couldn’t get back on our feet without Constitución, and Constitución couldn’t get back on its feet without us.”

The company has even opened its doors to curious visitors. “There are people who’ve lived across the road from the mill all their lives, yet who have no idea what goes on inside it,” Cerda says. “Letting them take a look around the mill has been crucial for building trust.”

As the recovery gathered pace, Elemental identified public buildings that needed to be rebuilt, or constructed from scratch, to enhance the city – including the fire station and bus station, plus a public theatre, school, public library and cultural centre. Again, the city’s residents were consulted: “We asked them to prioritise,” Aravena says. “Some said the bus station should be built first, for practical and economic reasons. Others had a more emotional response and picked the fire station, saying the firemen deserved it for the work they’d done after the earthquake. The point is that everyone has their own view. It’s not for me, as an architect coming from outside, to decide which is more important – a fire station or a bus station.”

The portico of the city’s new cultural centre. Photograph: Gideon Long

Elemental’s participatory approach also meant issues emerged that weren’t directly linked to the earthquake and tsunami. Some locals pointed out that the city suffered from flooding each year, and that this was actually a bigger problem than a tsunami which, though devastating, is likely to strike only once a generation. “We had no idea that flooding was such a big problem, which is precisely why you have to ask,” Aravena says. The architects incorporated a series of lagoons and barriers into their plans which should alleviate future floods.

Housing was a pressing problem too, and not only for the residents of La Poza. Hundreds of people elsewhere in the city had lost their homes. The government earmarked money for social housing but, as always, it was limited: Aravena and his team had only $10,000 to spend on each house.

“What do you do when you have so little money to build with?” he asks. “The traditional answer is that you build small, poor houses each measuring around 40m2. But we decided that instead of building a bad house, we would build half of a good house.”

The homes Elemental built measure 40m2, and include a kitchen/lounge, a bathroom and two bedrooms – but they can be expanded, at minimal expense, into a house exactly double that size. It’s an idea based on public-private partnerships: the state pays for the essential half of the house, and the owner can then expand it at their own expense, adding more bedrooms. It’s a design that Elemental has used elsewhere in Chile and which has proved popular.

It would be wrong to suggest that the rebuilding of Constitución has been easy or flawless. Aravena says he’s had to cut his way though miles of red tape to get this far. At Arauco, Kimber admits the company faced deep-seated mistrust from the local community. Local resident Chamorro complains that after an inspiring start in 2010, the reconstruction process has lost momentum. Everyone acknowledges there have been heated arguments along the way. Rival politicians bickering with each other has been part of the problem.

Within weeks of the quake, the centre-right was in power in Chile while the centre-left ruled Constitución itself. Now the situation has reversed: the centre-left runs the country but the city mayor is from a centre-right party. Hormazabal says this constant changing has blighted the reconstruction effort: “I worked with the last mayor, and whenever he asked for funding he didn’t get it. Why? Because he wasn’t from the ruling coalition,” he says. “I’ve also been in meetings called by the current mayor, and regional officials haven’t turned up, just because he’s from a different political party.”

Kimber complains that Chile’s politicians are too preoccupied with “results, inaugurations, and the need to cut a ribbon” – and are reluctant to take a holistic, long-term approach. Pérez, now the government’s representative for reconstruction in the Maule region, acknowledges there’s still a lot to be done in Constitución. “By January this year, 40% of the PRES projects had been completed,” he says. “But it would be a big mistake to try to put a definitive end-date on the process.”

There are plenty of other proposals in the reconstruction plan. Elemental is to build a footbridge to link the city with Orrego Island, site of a poignant memorial for all those who died in Constitución, and the architects also plan to improve road access to the city. Although tied to a tight budget, Aravena says money has never been his biggest worry during the rebuilding process: “The scarcest resource by far in cities is not money, it’s coordination.”

So how much has Chile learned from the earthquake and tsunami of 2010? The country is regularly hit by earth tremors, so will the response be better next time? And have its institutions improved to make the reconstruction process smoother? Aravena is sceptical.

“At the moment, when an earthquake hits, we have hotlines for the distribution of blankets, mattresses and shelters. We need something similar for public funding,” he says. “When a tragedy strikes, you don’t have time for a lengthy public bidding process. You have to allocate the work based on trust. The state needs to draw up a pre-approved list of consultants with a good track record, so it can go straight to them and get them on board. We need to build our towns and cities with future earthquakes and tsunamis in mind, rather than simply reacting when disaster strikes.”

But despite their frustrations, Aravena, Kimber, Pérez and Hormazabal agree that the reconstruction process in Constitución has been unique. No other town or city in Chile gave its residents such a pivotal role in the recovery process. Nowhere else has managed to bring together so many stakeholders, from both the public and private sectors, behind a single project.

If a similar earthquake and tsunami were to hit Constitución again, how would the city fare? Elemental’s Cerda says that once the trees have grown, the forest will do much to protect the city. “The water will flood the forest, but the waves’ power will be dissipated,” he says. “Of course the trees will die, their roots swamped by saltwater. But we can replant. The forest will act like a crash helmet. It protects your head when you fall, but then you have to replace the helmet.”

Five years on, memories of 27 February 2010 are still vivid. Pérez says he’ll never forget the sound of the tsunami crashing into the city: “Imagine putting a rock inside a bucket and shaking it like hell. That’s what it sounded like.”

Seventy-eight-year-old Chamorro still remembers waking up at 3:34am when the earthquake started: “I thought I could hear rain on the roof but it was the sound of tiles, cracking and falling to the ground,” she says. “I don’t know how I got out of the house. I thought I was walking across a carpet of broken plates. It was only afterwards I realized they were my CDs, scattered across the floor.”

As for Hormazabal, whose home was reduced to just six floor tiles, he has reconciled himself to never again living in La Poza. “We’ve all had to give a little over the past five years,” he says. “We’ve argued and we’ve fought, but we’ve also come together as a community. It’s been a real learning process for all of us.”

The scarcest resource by far in cities is not money, it’s coordination.

TED Talk: My Architectural Philosophy? Bring the Community Into the Process / Alejandro Aravena

“If there is any power in design, that’s the power of synthesis.”

In this TED Talk Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, the founder of ELEMENTAL, speaks about some of the design challenges he has faced in Chile and his innovative approaches to solving them. Emphasizing the need for simplicity in design, Aravena talks about three of his projects: the Quinta Monroy social housing project, through which he developed the “half-finished home” typology for governments to provide quality homes at incredibly low-prices; his “inside-out” design for the Pontifical Catholic University’s Innovation Center UC – Anacelto Angelini, which reduced energy costs by two-thirds; and lastly his masterplan for rebuilding a resilient coastline in Constitución Chile after the city was hit by the 2010 earthquake.

Aravena also emphasized the importance of community participation in his projects, saying: “We won’t ever solve the problem unless we use people’s own capacity to build.” Take a peek at one of his key projects below.

Quinta Monroy / ELEMENTAL

The Chilean Government asked us to resolve the following equation:

To settle the 100 families of the Quinta Monroy, in the same 5,000 sqm site that they have illegally occupied for the last 30 years which is located in the very center of Iquique, a city in the Chilean desert.

We had to work within the framework of the current Housing Policy, using a US$ 7,500 subsidy with which we had to pay for the land, the infrastructure and the architecture. Considering the current values in the Chilean building industry, US$ 7,500 allows for just around 30 sqm of built space.

And despite the site’s price (3 times more than what social housing can normally afford) the aim was to settle the families in the same site, instead of displacing them to the periphery.

If to answer the question, one starts assuming 1 house = 1 family = 1 lot, we were able to host just 30 families in the site. The problem with isolated houses, is that they are very inefficient in terms of land use. That is why social housing tends to look for land that costs as little as possible. That land, is normally far away from the opportunities of work, education, transportation and health that cities offer. This way of operating has tended to localize social housing in an impoverished urban sprawl, creating belts of resentment, social conflict and inequity.

If to try to make a more efficient use of the land, we worked with row houses, even if we reduced the width of the lot until making it coincident with the width of the house, and furthermore, with the width of a room, we were able to host just 66 families. The problem with this type is that whenever a family wants to add a new room, it blocks access to light and ventilation of previous rooms. Moreover it compromises privacy because circulation has to be done through other rooms. What we get then, instead of efficiency, is overcrowding and promiscuity.

Finally, we could have gone for the high-rise building, which is very efficient in terms of land use, but this type blocks expansions and here we needed that every house could at least double the initial built space.

SO, WHAT TO DO?

Our first task was to find a new way of looking at the problem, shifting our mindset from the scale of the best possible US$ 7,500 object to be multiplied a 100 times, to the scale of the best possible US$ 750,000 building capable of accommodating 100 families and their expansions.

But we saw that a building blocks expansions; that is true, except on the ground and the top floor. So, we worked in a building that had just the ground and top floor.

WHAT IS OUR POINT?

We think that social housing should be seen as an investment and not as an expense. So we had to make that the initial subsidy can add value over time. All of us, when buying a house expect it to increase its value. But social housing, in an unacceptable proportion, is more similar to buy a car than to buy a house; every day, its value decreases.

It is very important to correct this, because Chile will spend 10 billion dollars in the next 20 years to overcome the housing deficit. But also at the small family scale, the housing subsidy received from the State will be, by far, the biggest aid ever. So, if that subsidy can add value over time, it could mean the key turning point to leave poverty.

We in Elemental have identified a set of design conditions through which a housing unit can increase its value over time; this without having to increase the amount of money of the current subsidy.

In first place, we had to achieve enough density, (but without overcrowding), in order to be able to pay for the site, which because of its location was very expensive. To keep the site, meant to maintain the network of opportunities that the city offered and therefore to strengthen the family economy; on the other hand, good location is the key to increase a property value.

Second, the provision a physical space for the “extensive family” to develop, has proved to be a key issue in the economical take off of a poor family. In between the private and public space, we introduced the collective space, conformed by around 20 families. The collective space (a common property with restricted access) is an intermediate level of association that allows surviving fragile social conditions.

Third, due to the fact that 50% of each unit’s volume, will eventually be self-built, the building had to be porous enough to allow each unit to expand within its structure. The initial building must therefore provide a supporting, (rather than a constraining) framework in order to avoid any negative effects of self-construction on the urban environment over time, but also to facilitate the expansion process.

Finally, instead a designing a small house (in 30 sqm everything is small), we provided a middle-income house, out of which we were giving just a small part now. This meant a change in the standard: kitchens, bathrooms, stairs, partition walls and all the difficult parts of the house had to be designed for final scenario of a 72 sqm house.

In the end, when the given money is enough for just half of the house, the key question is, which half do we do. We choose to make the half that a family individually will never be able to achieve on its own, no matter how much money, energy or time they spend. That is how we expect to contribute using architectural tools, to non-architectural questions, in this case, how to overcome poverty.